Biography

by Robin Kinross, London, 2018

Among the founding figures of graphic design in Britain, Jock Kinneir was both typical and exceptional. Like other designers of this generation he went through art school, started out as a commercial artist, experienced several life-changing years in the armed forces during the Second World War, and then engaged in graphic design as a way of applying his visual and human skills in a society of scarcity and reconstruction, subsequently a society of growing prosperity and affluence. Yet Kinneir was also a unique, perhaps idiosyncratic figure: a man who thought from first principles with a natural intelligence, whose designing instincts ranged far beyond graphics.

Jock Kinneir was born at the Louise Margaret Hospital, Aldershot, Hampshire, on 11 February 1917, the son of Guy Kinneir (1892–1964), a second lieutenant in the Manchester regiment and an army doctor, and his wife, Helen Elizabeth Margaret, née Smith (1890/91–1956).1 But Jock’s parents separated when he was still a child, and he was then largely brought up by his paternal grandparents in Bexhill. His grandfather was also a doctor – another in what became a continuous, seven-generation line of Kinneirs who were surgeons. His grandmother Erna Kinneir (née Lund) had been brought up in Hamburg by her Norwegian father: she taught German to Jock, and seems to have been a strong cultural influence on him, encouraging him to go to art school and thus break with the family tradition of medicine. Jock Kinneir was emphatically international in outlook, and with a particular affinity for the north European countries.

The origins of the Kinneir family are Scottish, and ‘Jock’ was a given name (Richard Jock Kinneir). The name certainly matched the brevity and straightforwardness of his speech and manner: he was always on a level with the person he was speaking with.

After leaving Tonbridge school (in Kent), in 1935 Kinneir went to Chelsea School of Art as a student of engraving, illustration, and painting. It was there that he met Joan Illingworth Lancaster (1915–2008),2 a fellow student. They married in 1941, and after the war had three children, Elspeth, Ross, and Oliver. During his years at Chelsea, Kinneir was among the artists commissioned to paint the images for posters in the Shell company’s advertising campaign ‘You can be sure of Shell’. These two posters – which are simply pictures with lettering added – are the main traces of his work in those years.

Jock Kinneir served in the Royal Artillery regiment in the Second World War, fighting in the campaigns in North Africa and Italy, and in Burma. It is likely that he found a place in navigation and engineering work – he was very competent with the tools of calculation and technical drawing. Soon after the end of the war he worked as a designer at the Central Office of Information.3 This body, which grew out of the wartime Ministry of Information,4 was a principal point of focus for what was becoming identified as graphic design. Exhibition design was a large and important part of the CoI’s work, and its often complex nature – requiring the planning and co-ordination necessary for a construction project – became a good training for any aspiring designer. Kinneir went on (in 1950) to join Design Research Unit, which can be properly called the first British design group; founded in the war years it went on to become the pre-eminent design practice in the country. He once referred to DRU as a ‘finishing school’, through which many young British designers passed. The people in and around DRU played large roles in the Festival of Britain in 1951, whose primary manifestation was the exhibition on London’s South Bank, and which represented a culmination of the immediate aftermath of post-war British recovery. Kinneir designed the Polar exploration display within the Dome of Discovery.

In these years Jock and Joan Kinneir were raising their young family and were living on a converted infantry landing craft on the Thames at Cubitts Yacht Basin, Chiswick. It was from there that Jock designed their first house, built at Ham, within Richmond (now the London borough of Richmond). Although without any architectural training or qualification, he would have been able to express his ideas clearly in detailed drawings. In 1956 he left DRU to set up his own design practice, renting an office above a garage at 3 Old Barrack Yard in Knightsbridge. He also taught graphic design part-time at Chelsea School of Art (1954–1958).

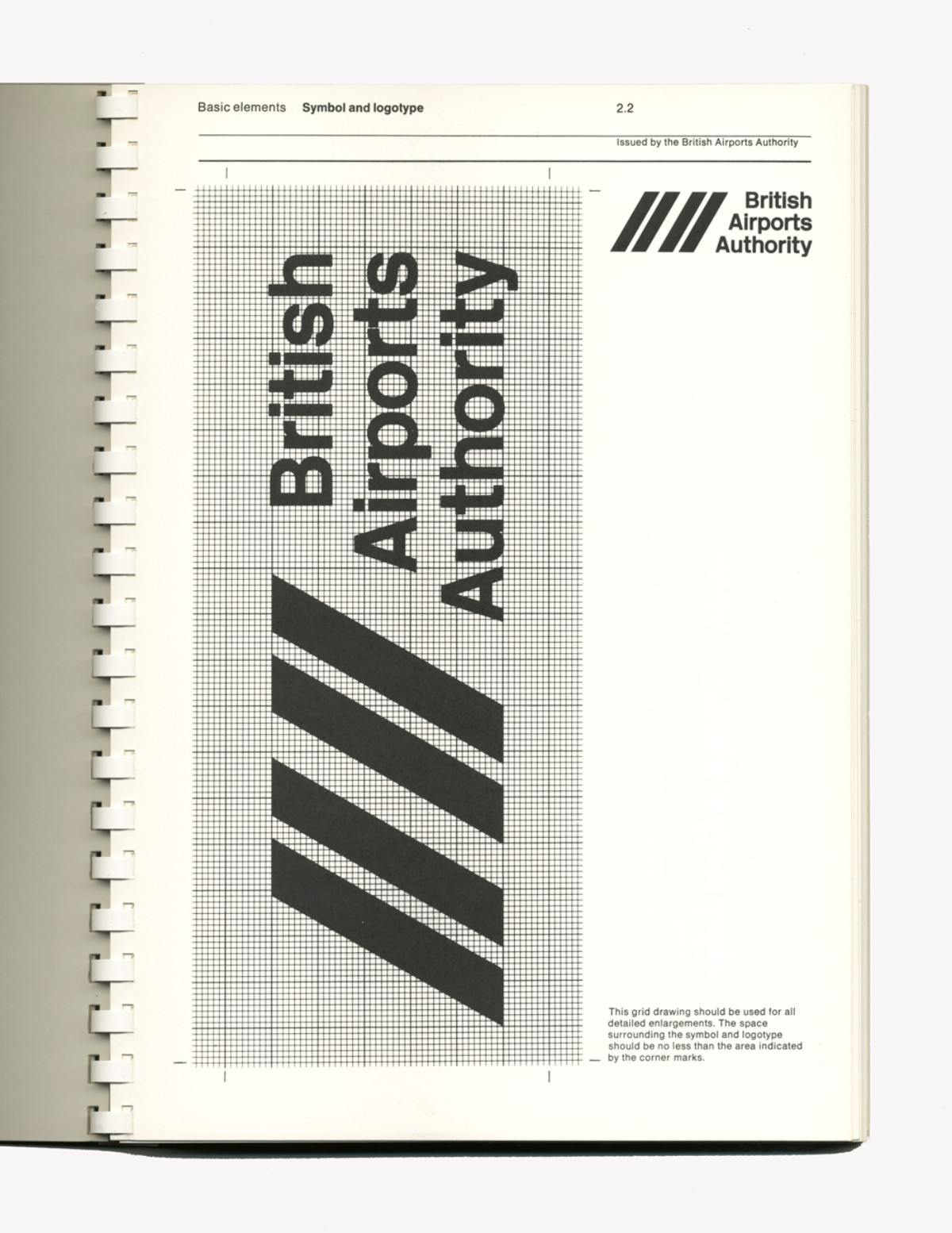

Jock Kinneir’s practice came to be known for its work on the design of sign systems for public transport, though it always also undertook less specialised, more general ‘jobbing’ graphic design work, sometimes small in scale. The sign work started in 1958 with the commission to work with the firm of architects (Yorke, Rosenberg & Mardall) who were designing the new airport at Gatwick. The commission followed on from a chance meeting with David Alford, a neighbour of the Kinneirs in Ham and one of the architects working on the job, who in that year became a partner at YRM. It was at this point that Kinneir asked Margaret Calvert to work with him as an assistant: she had been among his students at Chelsea School of Art and was just finishing there.

The Gatwick signs led on to another commission. Colin Anderson, chairman of the shipping company P&O-Orient line, saw the Gatwick work and asked Kinneir to work on a labelling system for his company. The job for P&O was essentially a matter of system design, manifested in abstract, coloured forms and simple headline text: the labels had to be understood by porters in many countries and needed to work without much text. In all this, it was an ideal preparation for the road signs work that soon followed. Colin Anderson (1904–1980) was a man of many parts and a member of a large number of committees and boards, among them (since the early 1950s) the Council of Industrial Design; he was enlightened about design and the part it could play in manufacture and in public life. In 1957 Anderson had been appointed chairman of the Ministry of Transport’s Advisory Committee on Traffic Signs for Motor Roads: the motorways would be a new kind of road in Britain, and the signs on them would need to be freshly designed for traffic moving at consistently greater speeds than on standard roads.

In June 1958, at Colin Anderson’s instigation, Kinneir was appointed to design signs for these new roads. The first signs were put up, as a trial for testing, on the Preston by-pass road in 1959. This sparked a public discussion and some dispute, including a counter-proposal by the lettercutter David Kindersley. Where Kinneir’s signs used a sanserif alphabet in upper- and lowercase, Kindersley proposed all-capital setting in a seriffed alphabet. Legibility tests showed no significant difference, and some on the Traffic Signs committee objected to Kindersley’s signs on aesthetic grounds. The committee was already working with its appointed designer and the work was continued to its conclusion.

The motorway signing work was published in a report of 1962. Before then, at the end of 1961, the project of designing a system of signs for the whole of the road network in Britain had been set in motion in the formation of a committee under the chairmanship of Walter Worboys. Like Anderson, Worboys was a businessman, and had served as chairman of the Council of Industrial Design. In his accounts, Jock Kinneir suggested that this extension from motorways to all the roads was always part of the plan of the ‘far-sighted and experienced’ civil servant who had initiated the work: ‘his technique vis-à-vis the Treasury was the old salami touch – slice by slice’.5 This was T.G. Usborne. It was decided that the new road signs should observe the protocols developed for continental European signs, notably the pictorial symbols and a more abstract symbology. The designers’ work was thus expanded well beyond their first concern with text and directional elements. In 1964, the Worboys report was approved by the Minister of Transport, Ernest Marples, and the new signs began to be implemented across the United Kingdom, later adapted and employed in other countries.

In 1963, Jock Kinneir was invited to become head of the graphic design department at the Royal College of Art in London. This committed him to working four days a week at the RCA. In his time in that position he was concerned to introduce a more professional quality to what was still a place of some amateurism. In 1969 he stepped down from head of the school to become a visiting lecturer, teaching one day a week (until 1973). Kinneir’s design practice remained busy. In 1964 Margaret Calvert became a full partner in what was then Kinneir Calvert Associates. The survey book 17 Graphic Designers London, published in 1963 by the printer Balding & Mansell, shows six pages of work by Kinneir Calvert. As well as the road signs and the P&O labels, there are symbols or logotypes – including the long-lasting Ministry of Transport testing station sign – designed by Kinneir, musical score covers designed by Calvert, a furniture catalogue by Kinneir, a house style by Calvert. As assistants became associates the practice shifted in its character too. In 1970 it had become Kinneir Calvert Tuhill Ltd. David Tuhill, who now joined as a partner, represented more clearly a strand of graphic design that had come to predominate in London, and with which Jock Kinneir never felt much affinity: a frankly commercial, ‘ideas’-based graphics that employed sharp copywriting and slick illustration or photography.

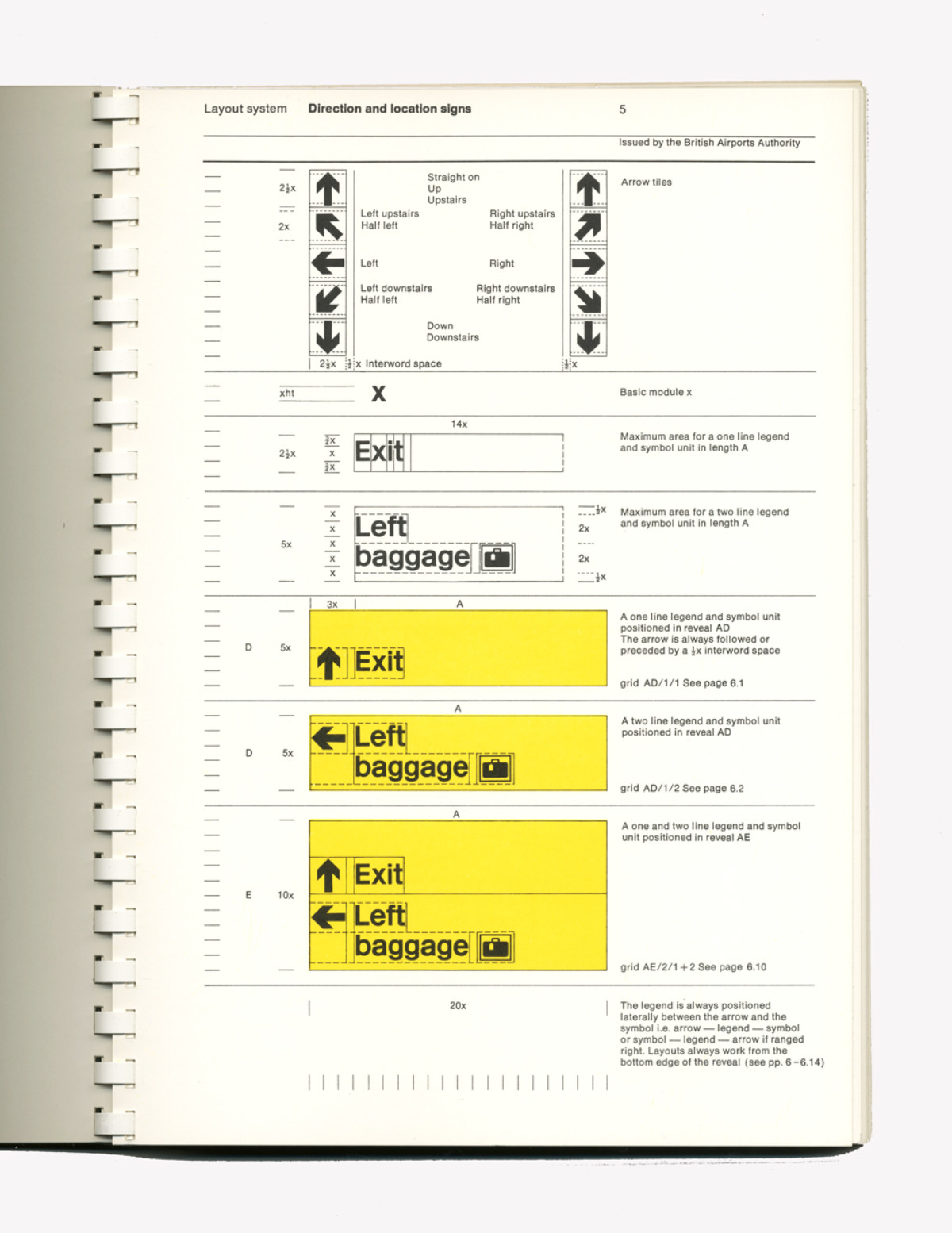

The public signing work continued. It included the sign system for British Rail (1964), designed within the larger house style that was being developed for that body by Design Research Unit; this was later adapted for use also on Denmark’s railway network. In 1964 Kinneir Calvert were asked to design a sign system for the new Glasgow Airport (designed by Sir Basil Spence, Glover & Ferguson). The work was extended to include a graphic house style for this airport – including uniforms. Further airport signing work followed, for Belfast and then in 1966 for British Airports Authority (initially responsible for Gatwick, Heathrow, Stansted, and Glasgow Prestwick airports). A sign system for British NHS hospitals was made later. In 1980 Margaret Calvert finished a sign system for Tyne & Wear Metro, from which she later developed a typeface for the Monotype company: this was the first of the practice’s signing letters to show serifs, as a slab-serif letter.

The letterforms that were used in these sign systems show a shift in style. The earlier projects – Gatwick, the motorways and roadsigns – relate in some respects to the British sanserif lineage that was exemplified by Edward Johnston’s London Underground letters. These alphabets have details and features that might seem ungainly, but which, in their avoidance of formal oversimplification, aid recognition. The later projects, starting with the British Rail alphabet, belong more to the German and Swiss sanserif lineage, which takes in the Akzidenz Grotesk and Helvetica printing typefaces. In his own testimony, Kinneir summarised the earlier sign systems as having been his work and the later ones as being primarily Margaret Calvert’s, though ‘we both together worked on applications and there was constant dialogue’. The letterforms were certainly important; perhaps even more important were the guidelines for their application. Here the success of the systems depended on clarity of instruction in making generalised guidelines, with which any individual sign might actually be designed and made. Jock Kinneir’s analytical and to-the-point habit of thinking and doing – developed no doubt in his years in the army and with the Central Office of Information – is evident in this fundamental aspect of the practice’s design work.

In 1980, aged 64, Jock Kinneir retired from full-time design practice, though he remained as a consultant on some of the continuing projects that he had worked on. Circumstances encouraged this move: the office rent had jumped, and he had suddenly lost sight in one eye. Despite operations, his sight in this eye was never restored. In that year he published his book Words and Buildings with The Architectural Press. This is a survey of its subject – signs and letters on buildings – and shows his analytical mind as well as his internationalism: the many examples in the book come from all over the world. He moved with Joan to live in the village of Winderton in Oxfordshire, in the second house that he had designed. Now far removed from the world of design in London, he drew and painted – working a series of pictures that documented winter flowering plants – and gardened according to organic principles. He also wrote a novel (unfinished) that he described as ‘a Chaucerian novel about politics’.

In the summer of 1994 Jock Kinneir became ill and suffered a serious heart attack. He died in hospital in Oxford on 23 August.

The Jock Kinneir Library would like to thank Robin for his advice, time and contribution to the Library.6

-

This information is taken from Jonathan Woodham’s entry on Kinneir in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online edition, accessed 19.3.2018). ↩︎

-

Joan was an artist and went on to write The Artist by Himself published by Granada Publishing, London, in 1980. Introduction by David Piper; designed by Harold Bartram; printed by BAS Printers, Hampshire. ↩︎

-

The Central Office of Information (COI) was the UK government’s marketing and communications agency formed in 1946. It closed on 30 December 2011 due to budget cuts during the Coalition Government. ↩︎

-

A government department responsible for publicity and propaganda during the Second World War. They oversaw campaigns such as the famous ‘Keep Calm and Carry On’ poster. Read more here. ↩︎

-

Jock Kinneir, ‘The practical and graphic problems of road sign design’, in: Ronald Easterby & Harm Zwaga (ed.), Information Design: the design and evaluation of signs and printed material, John Wiley, 1984 (at p. 341). ↩︎

-

Robin Kinross wrote one of Jock’s key obituaries following correspondence and conversations together during Jock’s later years. Paul Stiff details its publication here. “It [Jock’s obituary] was first published in a British national newspaper, The Guardian, on 30 August 1994. An extended and revised version, ‘Obituary: Richard Jock Kinneir’, appeared in Directions: newsletter of the Sign Design Society, vol. 1, no. 7, pp. 2–3. It is now much more easily found in Robin Kinross’s bracing collection of writings over the past 25 years Unjustified texts: perspectives on typography.” ↩︎